第13日目 - The book 第10.3節をよむ - lifetime - sin64を区間演算

10.2 Validating References with Lifetimes - The Rust Programming Language

ライフタイムとは参照に備わっているものである.型が推論されたり注釈が必要だったりするように,ライフタイムも注釈が必要だったりそうでなかったりする.

Preventing Dangling References with Lifetimes

The Borrow Checker

Borrow checker

Generic Lifetimes in Functions

文字列スライスをパラメータに持って文字列スライスを返すような関数.

fn longest(x: &str, y: &str) -> &str{

if x.len() > y.len() {

x

}else {

y

}

}

error[E0106]: missing lifetime specifier

--> src\main.rs:19:33

|

19 | fn longest(x: &str, y: &str) -> &str{

| ---- ---- ^ expected named lifetime parameter

|

= help: this function's return type contains a borrowed value, but the signature does not say whether it is borrowed from `x` or `y`

help: consider introducing a named lifetime parameter

|

19 | fn longest<'a>(x: &'a str, y: &'a str) -> &'a str{

| ^^^^ ^^^^^^^ ^^^^^^^ ^^^

This error indicates that a lifetime is missing from a >type. If it is an error

inside a function signature, the problem may be with failing >to adhere to the lifetime elision rules (see below).Erroneous code examples:

struct Foo1 { x: &bool } // ^ expected lifetime parameter struct Foo2<'a> { x: &'a bool } // correct struct Bar1 { x: Foo2 } // ^^^^ expected lifetime parameter struct Bar2<'a> { x: Foo2<'a> } // correct enum Baz1 { A(u8), B(&bool), } // ^ expected lifetime parameter enum Baz2<'a> { A(u8), B(&'a bool), } // correct type MyStr1 = &str; // ^ expected lifetime parameter type MyStr2<'a> = &'a str; // correctLifetime elision is a special, limited kind of inference for >lifetimes in function signatures which allows you to leave out lifetimes >in certain cases. For more background on lifetime elision see [the book]>book-le.

The lifetime elision rules require that any function >signature with an elided output lifetime must either have:

- exactly one input lifetime

- or, multiple input lifetimes, but the function must also >be a method with a

&selfor&mut selfreceiverIn the first case, the output lifetime is inferred to be the >same as the unique

input lifetime. In the second case, the lifetime is instead >inferred to be the same as the lifetime on&selfor&mut self.Here are some examples of elision errors:

// error, no input lifetimes fn foo() -> &str { } // error, `x` and `y` have distinct lifetimes inferred fn bar(x: &str, y: &str) -> &str { } // error, `y`'s lifetime is inferred to be distinct from >`x`'s fn baz<'a>(x: &'a str, y: &str) -> &str { }

Lifetime Annotation Syntax

ライフタイムはアポストロフィー'を先頭に付けて表すことが文法上のルールで,慣習的には他のジェネリック型と同じように短い文字,ただし小文字を使う.'aのような.参照(可変・不変)の&記号と元の型の記号の間に付ける:

&i32

&'a i32

&'a mut i32

ライフタイム自身は,注釈された参照がそのライフタイムの持つ有効期間を含むスコープ内で有効であることをコンパイラに教えるに過ぎない. その具体的な長さではなく,包含関係を注釈する.

Lifetime Annotations in Function Signatures

関数に実際に値が代入されると,それを持つ参照のうち最小のライフタイムがそのライフタイムの表す区間として確定する.

……用語が難しい! ”Lifetime”というが'aのような記号としてのlifetimeなのか,そのlifetimeが表すlifetimeなのか,

どちらも同じ語で表されるので何とも文に起こしにくい.むしろ混同というか同一視してもいいということか?

日和って「生存期間」とか使おうかという気にもなるが,訳しているだけで解決になっていない.

これはコンパイルする:

let t1 = String::from("foobar");

let t2;

let result;

{

let t3 = String::from("baz");

t2 = t3; //moved

result = longest(t1.as_str(), t2.as_str());

}

println!("{}", result);

これはコンパイルしない:

let t1 = String::from("foobar");

let result;

{

let t3 = String::from("baz");

result = longest(t1.as_str(), t2.as_str());

}

println!("{}", result);

おもしろいな.=の役割を捉えなおす必要がある.

Thinking in Terms of Lifetimes

返り値にライフタイムが含まれているなら,少なくとも一つのパラメーターがそのライフタイムを持っていなくてはならない.

Lifetime Annotations in Struct Definitions

So far, we’ve only defined structs to hold owned types.

参照ではない方の型を”owned types”というのか.

構造体のフィールドには参照を含めることもできるが,その場合構造体の定義中全てにライフタイム注釈が必要.

Lifetime Elision

唯一の引数の参照のライフタイムと戻り値のライフタイムが一致するときはライフタイム注釈を省略できる. Lifetime elision rulesといっていくつかのパターンではライフタイムは注釈無しで省略できる.

関数やメソッドのパラメーターに現れるライフタイムをinput lifetimes,戻り値のそれをoutput lifetimesという.

- (Input lifetimes) 関数の引数に複数の参照が現れる場合,それぞれ独立したライフタイムを持っていると仮定する.

明示的な注釈を与えた場合に

fn foo<'a, 'b, 'c>(x: &'a i32, y: &'b i32, z: &'c i32)となるのと等価.パラメータの数だけライフタイムがある. - (Output lifetimes) パラメーターにライフタイムがただ1つしか現れず戻り値が参照の場合,戻り値のライフタイムはそのライフタイムに一致すると仮定される.

- (Output lifetimes)

&selfを含むメソッドの場合,戻り値のライフタイムはselfに一致すると仮定される.selfが優先される.

この3つを適用して尚ライフタイムが確定できない場合,コンパイラは明示的な型注釈をプログラマに要求する.

Lifetime Annotations in Method Definitions

普通のジェネリクスと同様,ライフタイムもimplの直後に入る.

impl Foo {

fn my_method(&self, x: &i32, y: &i32) -> &i32 {

は

impl<'a, 'b, 'c> Foo<'a> {

fn my_method(&'a self, x: &'b i32, y: &'c i32) -> &'a i32 {

と同じことになる(たぶん)

The Static Lifetime

&' staticという,プログラムの全域にわたって有効であることを示す特別なライフタイムがある.

文字列スライスはこれを付けることができる一例.ただし,これを明示的に付けることは,たとえ可能であっても本当に必要か熟考するべき.

Generic Type Parameters, Trait Bounds, and Lifetimes Together

全部載せ.

use std::fmt::Display;

fn longest_with_an_announcement<'a, T>(

x: &'a str,

y: &'a str,

ann: T,

) -> &'a str

where

T: Display,

{

println!("Announcement! {}", ann);

if x.len() > y.len() {

x

} else {

y

}

}

まあ理解した感は無いな……実際にコードを書かないことには.

そういえば変数のスコープってエディタの拡張機能で色を付けたりできないのだろうか. いや,いや,スコープ自体は括弧で決まるからわざわざ視覚化するようなものでもないか?

sin

やるか……区間演算を.

昨日のアイデアを実現していく.

Interval構造体

まず「区間」を構造体として定義.

#[derive(Copy, Clone, Debug)]

struct Interval {

min: i128,

max: i128,

}

フィールドが2つともprimitiveなのでderiveでCopyトレイトをimplementできる.

CopyのためにはCloneも必要.Debugもderiveしておく.

今回は実装したいのはごく限定的で簡易な区間演算なので,区間に0を含むケースは除外する.もし含んでしまった場合パニクるように,初期化にはnewメソッドを用いることにする.

Interval{min, max}による初期化を禁じることはできないのだろうか.他の言語だと,コンストラクタをprivateにすることでできるが……?

さらに,minとmaxが逆転するケースも除外.こうすると区間に含まれる数の符号は全て一致するため「区間の符号」を定義できて,これをsignメソッドとする.

impl Intervalブロックはこうなる.

impl Interval {

fn new(min: i128, max: i128) -> Interval {

if min < 0 && 0 < max {

panic!("Cannot contain 0.");

} else if min > max {

panic!("min = {} < max = {} is not satisfied.", min, max);

}

Interval { min, max }

}

fn sign(&self) -> i32 {

if self.min > 0 && self.max > 0 {

1

} else if self.min < 0 && self.max < 0 {

-1

} else {

panic!("Contains 0 {:?}", self);

}

}

}

ここでsignのreturn typeをi32としているが,本当は列挙型で定義したかった.こんなふうにPos:正とNeg:負の二つのvariantsからなる:

enum Sign{

Pos,

Neg,

}

ところが,「列挙型のタプル」をmatch式のアームの中に登場させられないことに気付いて断念.こういうことはできない:

match (s1: Sign, s2: Sign2) => {

(Pos, Pos) => ...

}

1つ目のPosにassignされているため2つ目の登場が禁じられる.何かしら解決策はありそうだが今のところは見送った.

さて,Intervalに和・差・積を定義したい.今回は除算は不要.上のブロックにaddメソッドを単に追加してもよいが,演算子オーバーロードができれば嬉しい.

これに従ってやる.

数の+はどこでも使えるが,Addトレイトは明示的にuse文でスコープに入れてやる必要がある.あとで使うMul, Subも併せてこう:

use std::ops::{Add, Mul, Sub};

実装.

impl Add for Interval {

type Output = Self;

fn add(self, rhs: Self) -> Self {

Interval::new(self.min + rhs.min, self.max + rhs.max)

}

}

Selfが構造体の自分自身の型を表すために使えることを知った.ちょっと気になったのがシグネチャに参照が使えなかったこと.あれ,文字列スライスは?

String in alloc::string - Rust

ライフタイムか.今はCopyトレイトをimplementしているからいいけど,一般の構造体に加法を定義するときはこれを真似る必要がありそう.

同様にSubとMulもimplementする.

impl Sub for Interval {

type Output = Self;

fn sub(self, rhs: Self) -> Self {

Interval::new(self.min - rhs.max, self.max - rhs.min)

}

}

impl Mul for Interval {

type Output = Self;

fn mul(self, rhs: Self) -> Self {

let a = self.min;

let b = self.max;

let c = rhs.min;

let d = rhs.max;

let (min, max) = match (self.sign(), rhs.sign()) {

(1, 1) => (a * c, b * d),

(1, -1) => (b * c, a * d),

(-1, 1) => (a * d, b * c),

(-1, -1) => (b * d, a * c),

_ => panic!("unreachable"),

};

Interval::new(min, max)

}

}

mulメソッド内のmatch式でSign列挙型を使いたかった! 最後のアームはコンパイラ的には排除できないが原理的には到達しない.TypeScriptなら1|(-1)でリテラル型のunionを取るところなのだけれど.

ともかくこれで限定的区間演算が実装できた.

Frac構造体

分数を定義する.ただし表現能力は限定的で,

\[\begin{align} \frac{n}{2^{63}}, n = -2^{63},-2^{63}+1,-2^{63}+2,\cdots,2^{63} \end{align}\]という形の,\([-1,1]\) 区間内の有理数だけを扱う.つまり,両端除いて(\(\pm 1\)は排除してしまってもいいが)\(2\) 進法で小数点第 \(64\) 位以上が全て \(0\),整数部分も \(0\) の数.フィールドとしては分子のnだけを持てばよい.ただしこれを区間で定義する.

Interval同様Debug,Copy, Cloneトレイトをderiveして定義はこう:

#[derive(Debug, Copy, Clone)]

struct Frac {

num: Interval, //denom=2^63

}

numはnumerator.上の制約が満たされるようにnewにpanicを含めてメソッドを定義.

impl Frac {

fn new(num: Interval) -> Self {

if num.min < -(1<<63) || 1<<63 < num.max {

panic!("out of range")

}

Self { num }

}

fn to_u32(&self) -> u32 {

let min = integer::div_floor(self.num.min.abs(), 1 << 31);

let max = integer::div_floor(self.num.max.abs(), 1 << 31);

if min == max {

min as u32

} else {

println!("{:?}", self.num);

panic!("min={}, max={}", min, max);

}

}

}

ここでto_u32メソッドを導入.これは区間 \([a/2^{63}, b/2^{63}]\) で表される数の絶対値の \(2^{31}=4294967296\) 倍を返すメソッドで,RFC1321のこの処理を行うために定義する.

This step uses a 64-element table T[1 … 64] constructed from the sine function. Let T[i] denote the i-th element of the table, which is equal to the integer part of 4294967296 times abs(sin(i)), where i is in radians. The elements of the table are given in the appendix.

minとmaxそれぞれで得られる値が異なる場合パニクる.つまり演算に伴って蓄積する誤差が大きくなりすぎて精度が足りなくなったらおしまい.これを以下に小さくするかがアルゴリズム的には工夫のしどころになる.

そうか,時間計算量が減ることで誤差も減るのか.

「絶対値の整数部分」はfloorで計算できるので,numクレートを使う.

num - crates.io: Rust Package Registry

Cargo.tomlのdependenciesにnum="0.4.0"を追加してuse num::integer;.

FracもInterval同様に加減乗までを実装する.

impl Add for Frac {

type Output = Self;

fn add(self, rhs: Self) -> Self {

Frac::new(self.num + rhs.num)

}

}

impl Sub for Frac {

type Output = Self;

fn sub(self, rhs: Self) -> Self {

Frac::new(self.num - rhs.num)

}

}

impl Mul for Frac {

type Output = Self;

fn mul(self, rhs: Self) -> Self {

let num_prod = self.num * rhs.num;

let floor = integer::div_floor(num_prod.min, 1 << 63);

let ceil = integer::div_ceil(num_prod.max, 1 << 63);

frac_interval![floor, ceil]

}

}

この乗算による値の丸めが一番大きな誤差を発生させる.

Frac::new(Interval::new(min,max))が複数個所に現れるので,試みにマクロを定義してみた.

macro_rules! frac_interval {

[$min:expr, $max:expr] => [

Frac::new(Interval::new($min, $max))

]

}

macro_rules! - Rust By Example

よく分かっていないがRustのマクロは単に文字として展開するだけではないため安全で,拡張性もあってかなりクールらしい.

main関数

さてこれで構造体定義はできた.mainをえいっと書く.

const RANGE_MAX: usize = 64;

fn main() {

let mut sin = vec![Option::<Frac>::None; RANGE_MAX + 1];

let mut cos = vec![Option::<Frac>::None; RANGE_MAX + 1];

sin[1] = Some(frac_interval![7761199951101802512, 7761199951101802513]);

cos[1] = Some(frac_interval![4983409179392355912, 4983409179392355913]);

let print_data = |i: i32, frac: &Frac| -> () {

println!(

"{0},{1:#x},{1},{2},{3},{4}",

i,

frac.to_u32(),

frac.num.min,

frac.num.max,

frac.num.max - frac.num.min

)

};

print_data(1, &sin[1].unwrap());

for i in 2..=RANGE_MAX {

let s1 = sin[i / 2].unwrap();

let c1 = cos[i / 2].unwrap();

let s2 = sin[(i + 1) / 2].unwrap();

let c2 = cos[(i + 1) / 2].unwrap();

sin[i] = Some(s1 * c2 + c1 * s2);

cos[i] = Some(c1 * c2 - s1 * s2);

print_data(i as i32, &sin[i].unwrap());

}

}

\(\sin(i), \cos(i)\) をsinとcosに記録しながら順に \(i=64\) まで計算する.

長さの確定した配列を初期値なしで初期化することがどうやらできないようなので,Noneで初期化する.結局null初期化みたいなものだが手軽なのは良い.

let mut sin = vec![Option::<Frac>::None; RANGE_MAX + 1];

let mut cos = vec![Option::<Frac>::None; RANGE_MAX + 1];

気になる: Rustでメモ化を行うためのシンプルなライブラリを作った - 純粋関数型雑記帳

\(\sin1, \cos1\)だけは別のところで計算しておく.

sin[1] = Some(frac_interval![7761199951101802512, 7761199951101802513]);

cos[1] = Some(frac_interval![4983409179392355912, 4983409179392355913]);

は

\[\begin{align} \sin 1 &\in \left[\frac{7761199951101802512}{2^{63}},\, \frac{7761199951101802513}{2^{63}}\right],\\ \cos 1 &\in \left[\frac{4983409179392355912}{2^{63}},\, \frac{4983409179392355913}{2^{63}} \right] \end{align}\]ということ.テイラー展開に基づく厳密な評価.numクレートにBigRationalという任意精度の有理数の型があるのでこれもRustで計算できる.明日やろう.

ループ中では

\[\begin{align} \sin(2m) &= 2\sin(m)\cos(m),\\ \cos(2m) &= \cos^2(m)-\sin^2(m),\\ \sin(2m+1) &= \sin(m)\cos(m+1)+\cos(m)\sin(m+1), \\ \cos(2m+1) &= \cos(m)\cos(m+1)-\sin(m)\sin(m+1),\\ \end{align}\]によって順に計算.

for i in 2..=RANGE_MAX {

let s1 = sin[i / 2].unwrap();

let c1 = cos[i / 2].unwrap();

let s2 = sin[(i + 1) / 2].unwrap();

let c2 = cos[(i + 1) / 2].unwrap();

sin[i] = Some(s1 * c2 + c1 * s2);

cos[i] = Some(c1 * c2 - s1 * s2);

print_data(i as i32, &sin[i].unwrap());

}

加法定理は本質的には指数関数のべき乗だからこれはbinary exponentiationで,

\[\begin{align} \sin(m) &= \sin(1)\cos(m-1)+\cos(1)\sin(m-1),\\ \cos(m) &= \cos(1)\cos(m)-\sin(1)\sin(m),\\ \end{align}\]として直前の値を使うよりも積を取る回数が少なくて済む.ちなみにこちらを使うと \(i=59\) でパニクる.

Exponentiation by squaring - Wikipedia

データの表示にはクロージャを使ってみる.

let print_data = |i: i32, frac: &Frac| -> () {

println!(

"{0},{1:#x},{1},{2},{3},{4}",

i,

frac.to_u32(),

frac.num.min,

frac.num.max,

frac.num.max - frac.num.min

)

};

さてbuildして実行.CSVファイルに出力.

1,0xd76aa478,3614090360,7761199951101802512,7761199951101802513,1

2,0xe8c7b756,3905402710,8386788459767994236,8386788459767994240,4

3,0x242070db,606105819,1301602336180099913,1301602336180099922,9

4,0xc1bdceee,3250441966,-6980270972645063116,-6980270972645063102,14

---(略)---

61,0xf7537e82,4149444226,-8910863624203905422,-8910863624203904767,655

62,0xbd3af235,3174756917,-6817738567657275178,-6817738567657274498,680

63,0x2ad7d2bb,718787259,1543583886381157403,1543583886381158080,677

64,0xeb86d391,3951481745,8485742433882562732,8485742433882563404,672

RFC1321と見比べるとどうやら正しく計算できていそう.6列目の値はFracの分子の区間幅で,もともと \(2^{-63}\) だった誤差の拡大が \(2^{10}\) 倍のオーダーに留まっている.乗算1回で\(4\)倍に拡がるとして \(\sin(64)\) を計算するのに \(\log_2{64}=6\) 回の乗算が必要だから,\(4^6=2^{12}\) 倍に広がる,という見積もりはかなりいい線を行っている.

とりあえずRFC-1321のテーブルと一致するか確かめよう.

抽出したデータ.

rust-study/rfc1321_table.csv at main · roiban1344/rust-study

Pythonでやる.

import csv

range_max = 64

#RFC-1321から抽出したデータの読み取り

rfc1321_table = [0 for i in range(range_max+1)]

with open('rfc1321_table.csv', 'r') as file:

reader = csv.reader(file)

for row in reader:

i, t = row

rfc1321_table[int(i)] = int(t, base=16)

print(rfc1321_table[1:])

#Rustコードによる計算結果の読み取り

result = [0 for i in range(range_max+1)]

with open('out/data.csv', 'r') as file:

reader = csv.reader(file)

for row in reader:

i, t_hex, t_dig, lower, upper, width = row

result[int(i)] = int(t_dig)

if int(i)>=range_max:

break

print(result[1:])

#assertで両者が一致することを検証

for i in range(1, range_max+1):

assert(rfc1321_table[i] == result[i])

結果:

[3614090360, 3905402710, 606105819, 3250441966, 4118548399, 1200080426, 2821735955, 4249261313, 1770035416, 2336552879]

[3614090360, 3905402710, 606105819, 3250441966, 4118548399, 1200080426, 2821735955, 4249261313, 1770035416, 2336552879]

確認用のprintが表示されただけ.無事二つのデータが一致することが確かめられた.

データを眺める

ところで,このデータはどんな性質を持っているだろうか.ちょっとプロットして見てみる.

![Figure 1. i vs T[i]](https://github.com/roiban1344/rust-study/blob/main/sin64/i-vs-T_i.png?raw=true)

全くランダムではない.モアレ.視覚化すると楽しいがそこまで驚くような現象ではない.

\[\mid\sin(i)\mid=\mid\sin(i+\pi)\mid\simeq \mid\sin(i+3)\mid\]なので3個おきに繋がっているように見えている.

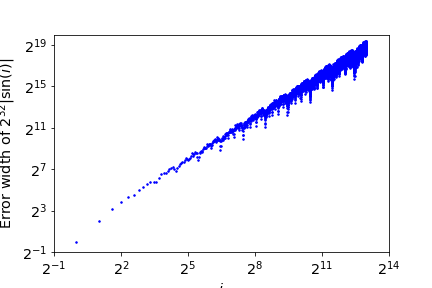

面白いのは誤差の蓄積.const RANGE_MAX: usize = 8192;に変えて分子の区間の幅がどう変化するか見る.

ちなみに今のアルゴリズムだとi=8195でパニクるのでこれがほとんどギリギリ.

Interval { min: 9111994663614257786, max: 9111994663614662833 }

thread 'main' panicked at 'min=4243103164, max=4243103165', src\main.rs:120:13

両対数で上下2本の直線上を行き来している.だいたい \(i^{1.5}\) か.分子の区間が \(2^{31}\) の倍数を含んでしまうと終わりなので,\(i=2^{13}\) くらいで破綻してしまうというのは割と理に適っている気はする.いやどうかな……パラメータを色々変えてやってみると面白いかもしれない.

rust-study/sin64 at main · roiban1344/rust-study

Jupyter Notebook上げたらLanguagesの比率が激変してしまった…….